Previously published in the ‘Fjord Herald’ Magazine – Winter 2014

(Part One in a Three-Part Series)

As a horse-crazy twelve year-old, I spent a month one summer on a crumbling estate set on the banks of the Ohio River. The stately Georgian mansion, once the home of a post-Civil War president, stood on a gentle rise above the river, surrounded by what seemed like miles of peeling, white four-board fencing next to a number of barns built in both the current and former century. The present-day owners of the historic property were typical horse people with big dreams but a frustrating lack of financing. Thus, a summer-camp for kids that had been bitten by the horse bug seemed a great way to fill the rooms of the enormous house with paying human boarders and thus help fund the string of Thoroughbreds in the yard.

There were a host of mares and young horses on the farm and the other campers and I spent most of our days generally annoying the mares and trying not to get kicked by the yearlings. After a morning of theory and lessons, the owners encouraged us to roam the fields, groom the horses and explore like the farm kids we all dreamed we were-with one exception. There was a quiet, isolated stall in a far corner of the cavernous barn that was ‘off limits’ because the stallion was in there! The other campers and I would huddle in a doorway down the aisle and listen to the enraged squealing, snorting and the dull thud of hooves striking walls when the grooms went to halter and lead him to the one and only diversion from his solitary existence – the breeding shed. That memory has stayed with me in subsequent years and when we purchased our first stallion, I promised myself that his life would be vastly different than that considerably sad memory.

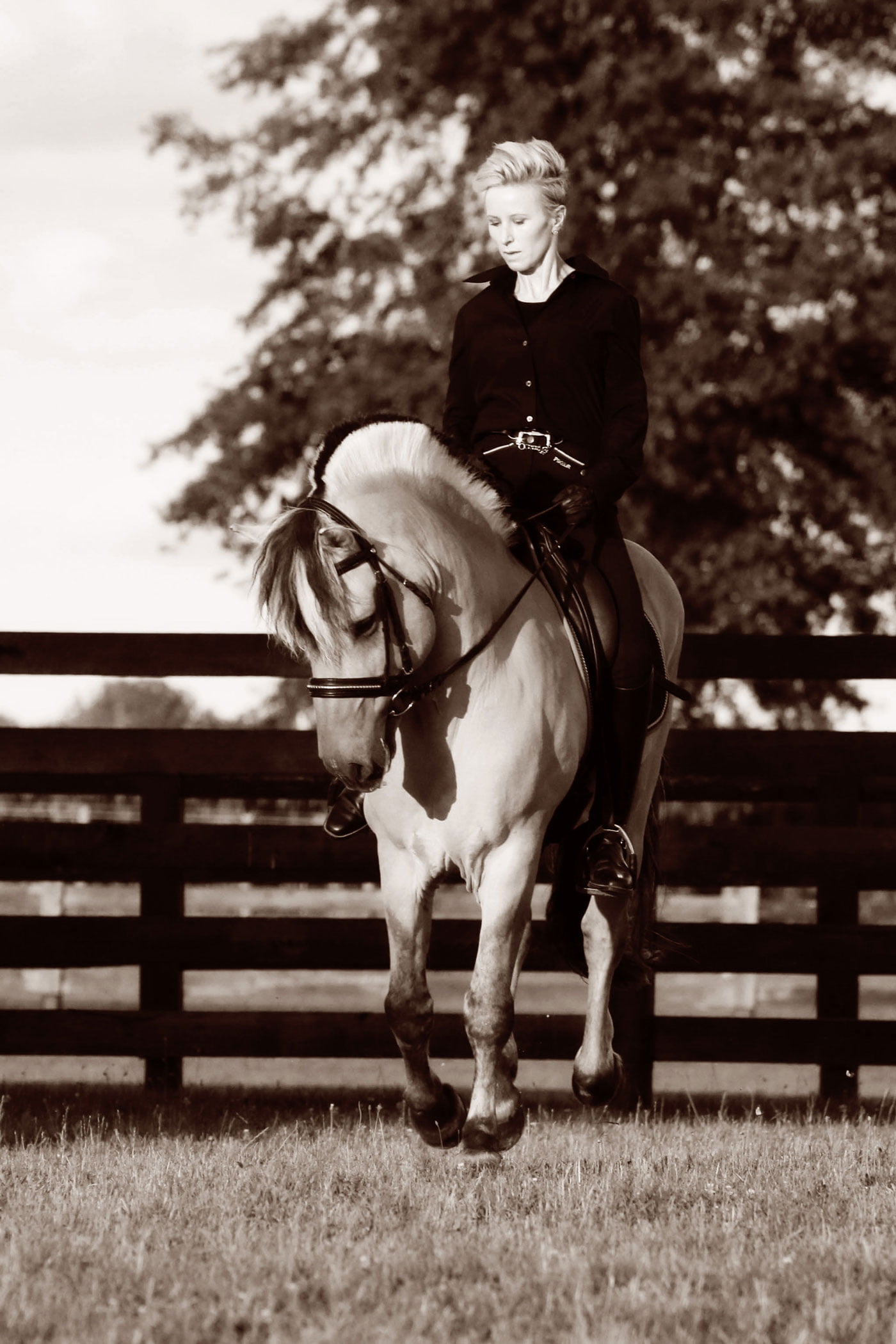

For the purposes of this article I will discuss our approach at Silver Drache Farm toward creating and maintaining content, pleasant, willing, working, fertile stallions that are as much a delight to the eye as they are under saddle or on the ground. Too often in the United States, stallions are consigned to being mere breeding machines and seldom leave their home farm. My philosophy has been that if I am forced by unforeseen circumstances to sell this horse, what will become of him? The market for a mature stallion that lacks under-saddle or driving training is extraordinarily small – and within the confines of the Norwegian Fjord breed, even more so. The less training and exposure a stallion has had, the more difficult he will be to sell should it become necessary. Gelding a mature horse is one solution to that problem but the potential buyer is still left with an aged horse that has few skills, making him nearly valueless in an already challenging market.

Physical Environment

We have a herd of eight horses; four of which are stallions. Our property consists of eleven acres. With space at a premium, we gave careful thought to how and where traffic aisles were designated and to the location of individual pastures and dry lots. Stallions present a unique challenge when it comes to farm design and layout. Fencing needs to be secure and safe, yet easily repaired. Stallions are notorious for challenging fences and we have had good success with four and five board fencing topped with a single strand of electric braid. Five board fencing can be set high enough to discourage most stallions in main traffic areas of the farm, allowing us to lead other stallions or mares comfortably. Inside the barn, traffic in the aisle is tight which requires two things in order to be successful: well-mannered stallions and confident handlers. Unfortunately, this works against us in soliciting barn help. Very few applicants have the skills to safely function in this environment, thus our quest for “‘good help” seems to be a never-ending process. It is my belief that a stallion barn is not an acceptable environment for youngsters or inexperienced adults as the risks of injury to humans and horses outweigh the benefits.

Tags: Fjord Horse Breeding, showing stallions, stallion management, stallion training